Fashion, Culture & Justice: A NYFW Dialogue

SPEAKERS

MODERATOR

PRESS

LIVESTREAM

TRANSCRIPT

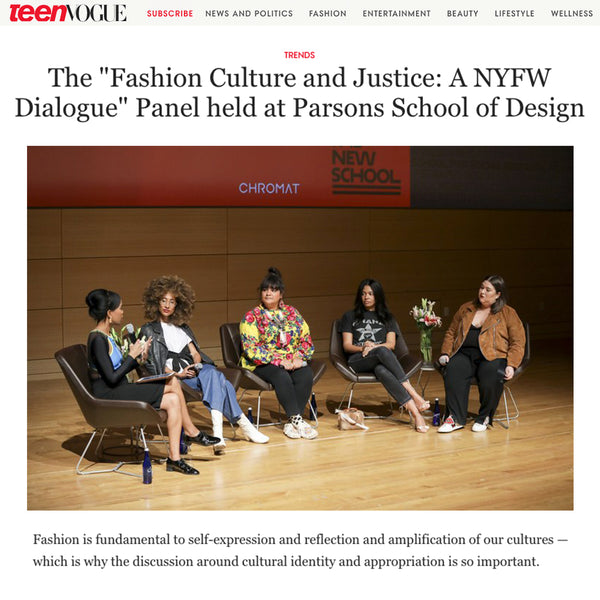

[Hazel Clark] Hi everyone. Welcome. I’m Hazel Clark and I’m Professor of Design Studies and Fashion Studies at Parsons. I’m really pleased to be able to welcome you all and to welcome this event and the panel.

So just a little bit of background: this event’s taking place during the fashion industry’s highlight in New York, which is Fashion Week. The event aims to identify, address, and deepen our understanding of the social and systemic issues that challenge and pervade the fashion system. So topics tonight that will be raised as a focal point will be solutions-based discussions, and will include subjects such as cultural appropriation and cultural sensitivity, and what fashion makes possible in a tense political climate.

The event is made possible through the support of Chromat and the School of Fashion at Parsons, and it’s also held as part of the Nth Degree, which is a curated series of events at the New School featuring thinkers, visionaries, and creators who bring about positive change in the world and redefine the cutting edge.

The series continues the New School’s century-long tradition of forward thinking by spotlighting lectures, performances, panels, and other public programs for curious minds. And for those of you who don’t know, the New School was founded, nearly a century ago in New York City by a small group of prominent American intellectuals and educators who were frustrated by the intellectual timidity of traditional colleges. The founders included Charles Beard, John Dewey and Thorstein Veblen, and they set out to create a new kind of academic institution, one where faculty and students would be free to honestly and directly address the problems facing societies in the 20th century. And that mission continues to be as significant in the 21st century as it was in the 20th, if not more so. There are many differences, one of the differences is the composition of the university. Over years the institution has changed and grown. In 1970 it encompassed Parsons School of Design. And over the last decade the university has integrated it’s subject areas more closely, to become a leading center of the social sciences, performing arts, art and design, and it continues to work across all the areas to reinforce its mission of intellectual freedom and social justice.

So as part of that mission, today we are turning that attention to issues of culture and justice, as they apply to fashion. And as a reminder on this poignant day of September the 11th, of how there continues to be a need for discourse and dialogue, and that today that’s more important than ever. So with that I’d like to ask our panelists to come out and join me.

[applause]

So I’m going to start in alphabetical order of last name just so there’s no confusion. I’m going to start with Amy Farid, who is in yellow, in the center. Amy has been a key hairstylist in several shows during New York Fashion Week past and present, including working with Hood by Air. Her clients also include Interview, Elle, 3.1, Phillip Lim, MIA, Chromat and Teen Vogue. She’s a member of the Osage tribe and also of Middle Eastern descent, and Amy also brings inspiration from her rich ancestry as well as from youth culture and the arts to her work, making her a unique creative force in the fashion industry.

And then Anastasia Garcia, who’s on the far right. Anastasia is a Latina photographer and body-positive activist based in New York City. She is most known for her use of photography to challenge exclusive beauty norms by using a range of diverse models, particularly plus-size models. She has published writings on the importance of diversity in media, and most recently starred in the film Straight/Curve: Redefining Body Image.

And then next, in the black t-shirt, is Aurora James, who is a fashion designer, a native of Toronto, and the founder of Brother Vellies. She has two specific goals in her work: to introduce her favorite traditional African footwear to the rest of the world, and to create and sustain artisanal jobs in Africa.

And the in the white, is Elaine Welteroth, who is editor-in-chief at Teen Vogue. Elaine is largely responsible for the expansion of Teen Vogue’s coverage to include a wide range of feminist, social justice, and political topics, alongside fashion, beauty and entertainment news. Elaine joined Teen Vogue in 2012 when she became the first African American ever to hold the post of beauty and health director at Conde Nast Publication.

And then finally, on my left here, someone many of you will know, Kim Jenkins. Kim is part-time lecturer in fashion history and theory at Parsons, and she specializes in the social, cultural, and historical influences behind why we wear what we wear, specifically addressing how politics, psychology, race and gender shape the way we fashion our identity, and I’m also proud to say she’s an alum of our MA Fashion Studies program. So I’ll hand you over to Kim as moderator, and enjoy. Thank you.

[Kim Jenkins] Thank you. Thank you all for being here. This is a pretty exciting moment for us. This event stems from a workshop that my academic partner and colleague Jonathan Michael Square and I had put on here at Parsons called Fashion and Justice. We put on a workshop in July here where we presented a daylong event where we lectured about the intersections of fashion and race. I positioned it in contemporary fashion, Jonathan spoke about the 19th century and enslavement, and the role that dress and the business of fashion plays in terms of justice, and just getting our registrants to think critically about fashion. So we had several people who had registered for the workshop and one of them was Becca McCharen-Tran, designer of Chromat. This entire event today is an idea of Becca McCharen-Tran. She spoke with me after the workshop and said we have to get this out beyond a workshop, out to the public and address these issues head-on with the fashion industry right in the middle of New York Fashion Week. And we put it together, and so here we are.

I’m very excited to be seated here with such a dynamic panel of women who’ve all agreed to address these issues here today. We will be discussing items like our cultural identity, cultural appropriation, personhood, solutions, more than anything, when it comes to addressing these issues in the fashion industry. And most of all at the end we’ve carved out about 30 minutes for Q and A for any questions you have because this is such a critical discussion and I want to make sure that we also hear from you and you’re able to engage in this dialogue.

So without further ado, I’d like to get into it here and let’s have conversation about fashion, culture, and justice during New York Fashion Week. So, I want to start with you, Elaine. I’m going to ask each of you about your cultural identity growing up. Is it something you always embraced? And in what ways it has shaped your work and the trajectory of your work?

[Elaine] First of all, hi everyone! This is so exciting. You’re so lucky to go to a school like this, for those of you who do go to this school. It’s beautiful, and I’m kind of a little bit jealous, I wish I came here. It’s my first time at Parsons, so thank you for having me.

Cultural identity, is it something that I always embraced? I would say as someone who came from a mixed-race household in a predominately white neighborhood, it was very hard for me to accept any aspect of being different. You know I think when you’re growing up you just want to blend in, and you sort of judge yourself based on like what’s around, that’s the norm, and sort of what media images are being projected, and so I have a lot of memories of examples of when I did not embrace my cultural identity or ethnicity.

I remember being a very young girl and begging my mom to get me this particular ballerina doll. My mom waited in line for hours and got me the doll of my dreams, and like, it was way too expensive for what it was, and you know, it was a pain in the butt for her. She got it for me and when I opened it, she saw me just kind of like, [gestures opening and closing the box] and say like thanks, and put it to the side. And she was like girl! I waited in this line, you’re going to play with this doll and your going to do it right now right in front of me and she’s like what is the problem? And I just said, ‘well I wanted the one in the commercial’. My mom bought me the black one. And there were things like that that I remember and it just pierces my spirit and my heart because the only reason I felt that way was because the blond white doll that was shown on TV was clearly presented as the superior version of that doll. The black doll was in the back.

So that being said, I think early on I recognized the power of images, the power of media, and so when I started at Teen Vogue as the beauty director I didn’t really walk into it with the sense of, that I’m coming in here to increase representation and start a conversation about race necessarily until I saw, on basically on day one, that the headlines read, you know, ‘Teen Vogue hires a black beauty director’, ‘first black beauty director in the history of Conde Nast in 107 years’. I didn’t know that, so I learned from the headlines, and very quickly I said,

"this is not a post-racial America. I will never just be good at my job. Or I will never just be the beauty director or the editor-in-chief of Teen Vogue. I will be always prefaced as the black one, the youngest one."

-Elaine Welteroth

And so those are things that I learned to embrace as I stepped into that role, and I saw that I had a unique power and a unique opportunity to do storytelling that no one else could do previous to me. I embraced that responsibility and my very first story at Teen Vogue was about embracing my curly hair, the bigger the better and just telling the story of my natural hair journey. Like actually learning to, this is the biggest my hair has been in my whole life, and I spent like 19 years of my life straightening it, using gel to keep it as small as possible. And I think that’s uniquely tied to cultural identity and where I was in my process embracing it, and so, yeah, here I am, big hair in my role as editor-in-chief and it definitely plays a part in the storytelling we do.

[Kim] That’s beautiful. Did you find that in doing that, you were kind of working that out on yourself once you were thrust into that role and embracing it?

[Elaine] I worked through all of that. I worked through all of that already. I think what I worked on professionally is leaning into it in my decision-making position. Leading the editorial vision with my race and not feeling ashamed about that. I think for a period of my career I wanted that to be secondary and it bothered me that was the first thing that people notice, but that’s the world we live in.

"My race steps into the room before I do."

-Elaine Welteroth

And so I need to embrace that, recognize that, and actually recognize the power in that. But in terms of like embracing who I am and all that stuff, I think I did work through that in college. So for those of you in college, if you’re not there yet don’t worry, give yourself some patience, you’ll get there.

[Kim] Amy.

[Amy] Hi! Hi everybody. It’s so great to see so many people here tonight for us in this space. Where we can all share these amazing stories. I am American Indian, Native American, indigenous, from the Osage Tribe, or Wazhazhe in our language. And I’m very honored to be up here with everybody and with all of you right now, so. What Elaine was talking about, you know, kind of coming into your own at a later age, you know I grew up going to our traditional ceremonial dances in Pawhuska, Oklahoma, which is where my mom lives back on our reservation, and you know you kinda take that for granted when you’re young, and you’re growing up. And you have all this beautiful culture all around you, but in those places in the Midwest you have this intense beautiful culture right beside intense white places and confederate flags and racism. And so you learn to navigate within those spaces really well and you don’t realize it until you come to this beautiful place called New York City- it is this beautiful freedom where you can engage with anybody from anywhere, and it’s so beautiful. And you see the diversity and it just makes your heart sing. And you can go after these goals of being this hairstylist I am now.

Growing up I was totally into fashion. I grew up 2 hours north of my reservation in Wichita, Kansas. And there’s not a lot of fashion victims like myself and so when I met my best friend, who was a Pakistani immigrant in ’94. I found him randomly at an after-school photoshoot for a thespian club yearbook which was really great. And we were basically like wait, you were the one who wrote that Dolce and Gabbana piece in the school paper? Cause I would be reading the school bulletin paper, I don’t know if you guys had this in high school, we had papers and there would always be pieces about Obsession Cologne and Kate Moss, and you know, this was 90s so you know, it’s like, amazing. [Laughter]

So, you know, it’s like Dolce and Gabbana, the Hippie Collection, I was like, who is writing this? Like who? I found him. And that’s my best friend, that’s my boo. And so we started taking our beautiful friends in high school and shooting them, and like, emulating these editorials that we were seeing in Vogue and Bazaar in the 90s and they’re still really beautiful pictures. And so I found, back there, I found my creative outlet, where my passion was. And you know, my mom didn’t quite understand it, she was like you’re playing dress up. And I was like, yeah I am, but I think there’s something there.

I didn’t have a role model or a mentor. There was nobody really doing what I did that I knew that looked like me or that I saw, you know, I had no awareness of that, and I didn’t care. And it’s so amazing when you’re young and you’re just kind of like: I have to do this. There’s no other option, something’s going to, you know, help me do this and it’s the universe and when you put it out there helps you and it did.

Shiraz, my photographer friend ended up moving to LA and I went out to LA and hung out for a little bit. And ended up having this like revelation on the beach and was like sun gazing and burning my retinas. And the universe spoke, and it was like girl, go back to hair school, get your cosmetology license and then move to New York, and do this, do what you want to do. And that’s what I did! I went home, moved back in with mom, I think I was like 19, and then got on a Greyhound Bus in the year 2000 and from Witchita Kansas I came to Port Authority. I had only heard of one place in New York to work, because I had read credits in magazines, and it was called Bumble and Bumble. And I was like, they have a salon! Oh it’s perfect! You know, and I was very fortunate. I had great older gay men that helped me lie on the resume and made me sound fab. Mind you, like you know, like I’m trash. I have no qualifications whatsoever. But you know I had an eye and I had that drive, you so I was like I’ll do it. So I got this job, right, and I started assisting, and that was it. And I kind of, it was just this path that helped me, and I think it’s just,

"I didn’t have someone to look up to. It was like, it’s up to me or no one."

-Amy Farid

This is my life. This is what I’d rather do. So I had nothing to lose. I was very thankful. I was raised by an amazing single mother who did her best and let me be creative and drive her crazy. Completely nuts. And she supported me and still supports me so much. I’m super thankful for that. So, yeah, I had no one else, so that was my drive to have to do this.

I didn’t realize that till recently when we had a panel discussion at the Museum of the Native American where they were asking me similar questions about mentors, and who you looked up to and I was like, [whispers] wait, there was no one. It was me! I’m the one! So I’m the one! So I did it!

"So maybe there are other young native brown girls that are seeing this and be like, you can do it too."

-Amy Farid

[Kim] Aurora? How has your cultural background shaped your career?

[Aurora] I’m from Canada, a very special country. And I think what was a little bit different about me is my mom was adopted at birth, and my dad passed away when I was very little and I didn’t know any of his family. So growing up when it came to what my actual background was, my mom was like well I don’t know what mine is because I was adopted at birth and your father’s from Trinidad. And I was like okay, so I’m like Trini and white. And so I kind of rolled with that. And then when I was like 16, my mom was like, so I took a DNA test. And I was like okay great what happened? And she’s like I’m Inuit and Irish - so we’re Inuit and Irish. And I was like okay so I’m Inuit, Irish and Trinidadian, and she was like Trinidadian? And I was like, yeah! Like, you know, that’s what dad was. And she was like oh no, no, he was from Ghana. And I was like, but hold on, like, we lived in Jamaica for like three years, I thought I was an island girl!

And she was like, you can be whatever you want to be, girl. And I was like, but this is major. And she’s like, why, do you think that it makes you different than you thought you were? And I was like, I guess not. And she was like I’m adopted at birth. For all you know the person sitting next to you could be your brother’s sister mother.

"You have to explore all identities like they could be your own, and you have support all identities like they could be your own."

-Aurora James

So that was very much sort of how I came into the conversation about culture. We spent a lot of time growing up like visiting different communities and learning about different cultural apparel. She had an amazing collection of fantastic kimonos, and Dutch cloths, and she would kind of talk me through all these different things and why they were important and why they shaped and built heritage. And even when I was younger before she found out that she was Inuit, we would always visit some of the reservations in Canada and we would look at amazing beading. And like how they used the deer and ate the deer and then turned that deer in to a pair of moccasins. So that conversation has definitely been a big part of my life for sure.

[Kim] And so with your work, was that almost intuitive for you, this kind of fluidity you kind of have with identity and geographical location with the work that you end up doing with artisans?

[Aurora] Yeah I think it was kind of inevitable because for me, I started traveling through Africa in my mid-20s. The first place I ever went was Morocco, Nigeria, then Namibia and on from there. I was seeing all these amazing artisans making these things and I was like I’ve seen this in fashion magazines before but not this good. And I don’t think that you were involved in that, I feel like it was done at a sweatshop, but this is better. And I feel like we can do something with this.

I went through a phase where I became really disenfranchised with fashion, because my early experiences with it didn’t involve empowerment.

"Being a woman of color and being a woman who struggled with my own identity and feelings about myself and who I was and my place in the world, I didn’t feel better going through fashion magazines, I felt worse about myself. So I knew for me to make a return to fashion, I would have to do it in a way where I could let the industry that I love empower women in the process. That’s why I created Brother Vellies."

[Kim] Anastasia

[Anastasia] My family comes from a small town in Puerto Rico called Ponce. I grew up on Military bases, so we traveled the world my whole life. Every base we went to, they would have Hispanic heritage committees and each community had that. So being Hispanic was always part of my life. No matter where we went in the world- Japan, Germany, it was always a part of my life.

It was always interesting because I am white presenting in a lot of ways. I always felt a million percent Hispanic my whole life- family is so much a part of my life. But people were always like ‘you don’t look Spanish’ and it was always a weird thing. It didn’t start to come out in my work until I starting photographing.

"I always knew my body was an anomaly in fashion, and if you add any other race besides white to that body, it becomes an even smaller margin of what’s represented in media."

-Anastasia Garcia

When I became a photographer, moving through school before I graduated, I understood that models looked a certain way. And if I wanted to be successful in the fashion industry, I would have to shoot a certain type of woman. And I didn’t even question it, because I just wanted to be a great fashion photographer, and I didn’t see any other fashion photographer shooting many models other than what had historically been presented.

Once I started making the decision to- first of all accept that I was fat, because I didn’t know-

"I realized that it was my responsibility as a photographer to be cognizant of the work that I was creating and make sure I was representing diverse bodies and also representing diverse races."

-Anastasia Garcia

Because I believe that body diversity and race are intersectional. I didn’t see any woman, maybe my family members who weren’t as plus size as I was- but I didn’t see their bodies being represented in media either. So, I realized that if I was going to focus on any kind of diversity, I needed to be cognizant of all diversity and I needed to acknowledge the responsibility that I had as an image maker and really create images that weren’t going to damage people the way I was damaged by media.

[Kim] I think this provides a great segue into how you discovered that the work that you’re doing- and you may not have even thought about it at the beginning- how it had a social impact and who you were reaching, inspiring, influencing. At what point did you discover that you had a social impact?

[Anastasia] I was working for an ecommerce conglomerate and I was sitting around a table having a discussion about what project will come forth. The business was talking about launching their plus size division. I was sitting around a table full of people and everyone was like ‘Oh we should take these plus size clothes and shoot them on straight-size models and just pin them to fit.’ It was like this record screeching sound in my head- I was fresh out of college, I was 22 years old, sitting around a table full of people who were much older than me. And I was just like ‘NO!’ and it was one of those movie moments where everyone turns and looks at you and I was like I’m 22 and you guys are going to kill me. But I was like ‘you guys cannot expect to sell to a customer and then pin them on this woman who they can’t relate to at all’.

It was the first time I realized the power of being seated at the table behind the scenes. We’re so focused on who comes in front of the camera, we’re so fascinated with models and celebrities, but

"we don’t always consider the conversations that happen behind the scenes that put this work forward,"

-Anastasia Garcia

and that was the first time that I realized that as an image maker, I had the opportunity to have those conversations. It started all of that.

[Amy] I started to realize my impact during Fashion Week, seeing the work that I do for Hood by Air and what we do to the models backstage. [How we] transform them. Shane always casts kids through street casting, not necessarily models. We don’t want to portray this image of ‘this is how one should look in clothes’, we want to have this dialogue of someone that’s coming in and putting a super masculine man in a dress. And then I give him feathered hair. Having that as a platform to see these juxtapositions with gender really spoke to me and I got a lot of press because of that. Really good press. And confused. Early on, before we became so woke as we are now, a lot of great things were happening in this world and in fashion too that we had this platform to turn things upside down, especially in New York.

NYFW is none for being super minimal, known for doing a ponytail, hair-wise it’s very simple, easy hair, a ponytail, or how New Yorkers do our hair- a top knot. With Hood by Air we really got to mix things up a bit and that was when I first realized the impact of that- seeing this imagery with people- mixing up the stereotypes and turning those upside down. And I’ve done a lot of interviews about that and I felt good in that this was something that needed to happen, that is happening so much. Just opening up gender and whatever gender is. That was when I first realized my impact.

[Aurora] For me, I noticed the impact in Africa. We started with this shoe called a vellie, or as South Africans call it the sellie. It was like this tragically unhip thing to wear in Africa- no one wanted to wear it. They thought it was like a cursed shoe. I was like ‘this is a traditional shoe’, and they were like ‘no, we want to wear what Kanye’s wearing’. I was like ‘Kanye would wear this’, and they were hysterically laughing at me like no he wouldn’t.

So for me, having that shift happen with them, when they saw Kanye come to our first presentation, and they saw celebrities wearing traditional African shoe shapes and shoe styles that were made by them, it completely changed their value of their work and their perception of themselves. And that created an entire shift in South Africa when it came to their own cultural clothing, they were like ‘wait a minute, we don’t have to aspire to this, we can revel in the beauty of what we already have. And we are the creators of these ideas, and everyone else is pinning pictures of us to their mood boards. And we don’t have to just be inspiration or pinterest swipe anymore, we can be part of this narrative and dialogue’. So a lot of things have shifted within Africa. Sometimes I’ll do sketches and send them to Africa- I work in many places in Africa- and I’ll send the different workshops and they’ll send back a sample that is completely different than what I did, and they’ll be like ‘well yours wasn’t good, this one is better’. And I’m like OK! Get it! You do you, you’re the one who’s making it and we’re basing it on the skills that you have, so if you didn’t like the beading that I came up with, by all means let’s do your beading. Because you know better than I do, so it’s really about empowering people in the process.

"When you empower someone to be part of the conversation, that’s when you really see a difference."

-Aurora James

[Kim] Did you notice a shift in when you engage with them as a woman in color, and this might be speculative, as to how they regard you, versus a different designer coming in to use their skills and resources?

[Aurora] It’s very country specific. Their reaction to a woman of color in South Africa is extremely different than it is in Kenya. And sometimes its not even about color, it’s about a woman. Early on in Kenya, I had big problems being a woman, I felt like I would need a man saying the same thing I had just said in order to get anything done. In South Africa, they were hyped. They were like this is a person of color and she’s designing things and she’s telling people what to do and we’re all about it and we’re going to get these shoes out everywhere and nothing could stop them. I could have been a woman; I could have been like a teeny tiny toddler like that was like ‘c’mon guys,’ as long as I was a person of color they were like on board. [laughs] I wish I was a teeny tiny toddler when I started.

[Amy] Can we do that? I have a seven year old, is that too old, that’s not a toddler anymore?

[Aurora] Start ‘em young

[Amy] Let’s do it

[Aurora] I’m not for child labor just to be clear

[Amy] Oops sorry, can we cut that?

[Aurora] Its called Facebook live, there’s no going back.

[Kim] Elaine please tell us how there was sort of a pivot with your publication [Teen Vogue]. When did you start to realize that it was time to take things to the next level and become sort of politically engaged, and that your work had the potential for some crucial social impact?

[Elaine] Well first and foremost, as a black woman, I understood the politics of hair and beauty, and I started at Teen Vogue as the beauty director, and from the very first story recognized that all I wanted to do was tell stories that only I could tell because I recognized there was a need for them in the market. I came from a black magazine initially, I think part of me when I left that magazine,

"I felt like there was a pressure- probably self imposed- to assimilate in order to ascend,"

-Elaine Welteroth

and I realized coming into Teen Vogue that it was actually the very opposite, it was like stripping away the thought that I need to assimilate that actually helped Teen Vogue to shine, and helped me shine, and helped me find my voice as a journalist.

It was through forward stories first and foremost about the politics of black hair at a mainstream, youth oriented magazine. I remember the first time that as the beauty director I did a piece that I felt like needed to be done, of course it could be controversial, I don’t know if people were going to get it. It started with me leaning into the table as a black woman and speaking about cultural appropriation, and starting a dialogue or contributing to a dialogue that was already existing within our team about what it is. There were a lot of people on my team who really didn’t understand what cultural appropriation meant, and I think as one of the few or one of the only black women or people of color on that team at that time- things have changed a lot since then at Teen Vogue-

"I had a choice there whether to say ‘I’m tired of being the black representative, I’m tired of being the only one explaining something like this for an entire race or many different cultures’, or owning that and saying this is an opportunity, this is a teachable moment for our whole team and potentially for our audience, so we have to create a safe space at the office first and foremost to talk about this stuff’."

-Elaine Welteroth

These are image makers, these are storytellers, and if they don’t know what this means, then we are going to be a part of the problem, we are perpetuating this issue.

We did a story, we ended up calling it “cultural appreciation,” because people were accusing us of culturally appropriating, and we kept seeing it every fashion week- designers being under the same attack, and you know some people in the audience didn’t understand it and I was like ‘I get this, we have got to work through this together’, so we ended up doing this story where we wanted to cast a girl from different backgrounds who have looks that are routinely appropriated at Coachella or on the runways and we want them to explain to our audience - their peers - what cultural appropriation is and what the difference is between cultural appropriation and cultural appreciation.

At that time I don’t think Teen Vogue or any mainstream media publication was really like considered an authority on the matter, so for us, we weren’t going to write the final word on cultural appropriation, so we were like ‘Teen Vogue is a platform to amplify the voices of young girls and young people’ so lets contribute to the conversation through them. I remember we were like we definitely need a Native American girl in the mix because that’s one of the biggest conversations around Coachella, you know wearing feathers, and people on my team were like ‘really you’re just going to find a Native American girl walking down the street in New York City?’ and I was like ‘Yes. We will.’ [and they were] like ‘Good luck girl,’ so we hired a street caster and we found an amazing array of young women, including a Native American girl Daunnette, who was fantastic.

She came with her headdress that no one could touch on set except for her mom. She explained to us what it meant, and the significance of it; how she earned it, and why it is so offensive to her when she sees it being appropriated by white people at Coachella who wear it and have no idea what the significance to her culture is. We all learned. So it was really rewarding just on a personal level to be able to have our whole team partner on this issue and everyone gained from it.

When the story went live, we didn’t know [what to expect]. People could have dragged us. We didn’t necessarily have the trust of our community to speak as an authority on social justice or cultural appropriation, any of this. We did these videos with each of the girls explaining what this meant to them, and it was the first time a beauty story went viral. When it became a Twitter moment when that was a big thing, we knew that it was a really good story.

I was scared, because I was the black beauty director, so if something goes wrong in any way, I am taking one for the team. It showed us that it is a need for more content like this, and they do want it from us as long as we do it the right way. So it was really empowering for our whole team, and it changed the way we approached storytelling in general, but particularly with beauty and fashion,

"recognizing the cultural significance we can have through the lens of beauty and fashion. Previous to that, beauty and fashion seemed like frivolous topics, but they’re so politically charged."

-Elaine Welteroth

That was kind of the beginning of when we started leaning into that. As you know the brand has evolved a lot since then. I think you guys are all hopefully paying attention to Teen Vogue, so I don’t need to explain. I feel really proud that we are the platform that allows young women and young people to be both.

"We all contain multitudes, and you can love fashion and love beauty and also care about what is going around in the world around you, and be incredibly politically active and engaged in political conversations in your communities."

-Elaine Welteroth

We’re not shying away from fashion, we’re not shying away from the love of creating and celebrating designers, but I think there’s a reset and a balance as a storyteller today in 2017, especially talking to a particular audience, which is extremely- I hate the word woke now. I’m so over it, we need to come up with a new word today, that’s the assignment. When my white father started to say the word woke I was like “that’s how I knew this is done. It’s over.”

[Amy] That’s awesome. Elaine I wanted to tell you, I was on a metro north train, and I was getting off at my stop, and I see this huge ad and it was the back of the Native girl’s head, so it was the eagle feather with her bead, and she had her hair wrapped. It said- I don’t know what the little tagline was- but you can’t see if this was a Native girl, but it looks authentic, that’s a real eagle feather. I have them, I know what it is, but I didn’t know. It was just a beautiful crop of the back of her head, and I was just like “no Teen Vogue, don’t do this to me.”

[Elaine] They didn’t trust us

[Amy] I literally thought: okay they got a feather, the hair was a little messy. Native girls like it tight, you know when you dance. I was like now I have to drag, then I did my research, and I was like “oh my god, this is so amazing” and I was part of the twitter moment and I was re-gramming and re-facebooking—whatever you do. There was another one about misconceptions and stereotypes about Natives, like ‘we all get paid for this’, or Thanksgiving and so I reached out to those girls and they were like ‘oh my god thank you for sharing our video,’ and I was like ‘you guys are amazing,’ I’m so proud.

"So even at 38 years old, I’m not used to seeing that imagery, so thank you, that’s so dope."

-Amy Farid

Thirty eight and I’m in the Stockholm Syndrome, I’m still so used to not seeing representation, and like even fearful of like “oh no they’re…” so thank you, that’s awesome.

[Elaine] Can I just say something, first of all you’re trying to make me cry up here.

[Amy] Girl I’m the crier so let’s do this. Let’s go Oprah. We need a show I’m ready. We were talking about going on a world tour after this. Girl she thought we sold out, and she was like “how much were tickets?” and I was like “girl it was free.” So we ain’t getting a cut? [laughs] Next time. This was the beta next its real.

[Elaine] I just want to say thank you for doing your research after seeing that picture just seeing the headline.

[Amy] Do your research.

[Elaine] I can’t tell you- I know now I’m answering the question double time, but I’ll make this one quick. The very first time I recognized my impact was not a great experience because the culture around news today is just headline driven, and just so many people see something on Instagram, or see someone’s opinion on Twitter about a story they’ve never read. Its just retweet, drag, repeat, and it’s so problematic. So the first time—I wasn’t going go here but now I’m going to go here.

The first story I did where I wanted to lean in to talk about the politics of black hair was after my first trip to Africa. I went to Rwanda and Ethiopia, and I got my hair braided by locals. I came back to Condé Nast with that hair and the comments that I got, and the looks that I got were just something to write about. It was right around the time that Zendaya went through her Oscars moment with Giuliana Rancic [who criticized her dreadlocks]. There was a conversation brewing, and so I was like I have something to contribute here so we did a shoot with a young model with Senegalese twists like my twists. I’m biracial, and I wanted a model who was also biracial because I was talking about leaning in for the first time in my life, embracing my African heritage and going to Africa and wearing my culture and my heritage on my head as a crown, and coming to work and the reaction I got, and I wanted all of that.

"There were layers, there were levels to this, there was nuance. Nuance doesn’t translate very well on social media."

-Elaine Welteroth

And I felt so proud of it. It was like the first time my whole team was just following my lead blindly like ‘okay Elaine we’ve been dragged before for stuff like this, but we trust you’ and I’m like ‘I assure you this is the right way, we have to tell the story, it’s so important,’ and it was about how beauty is also activism; it can be activism. So the story goes out, and someone with like 100 followers on twitter posted a flash picture of the photograph of the model with the caption that says “Teen Vogue culturally appropriating once again. You should be ashamed of yourself.” They thought the model was white because of the flash and she was lighter skinned. She was about my complexion, I mean—she was a brown girl. So then it got retweeted hundreds of times, and it became a headline on the Daily Mail “Teen Vogue writes anti-black story”. I’m like how does it make the Daily Mail without anyone reading the story, how does that even happen? It got picked up by USA Today, it got picked up everywhere. My phone’s buzzing on set, and you know everyone would say ‘leave it alone, let it go, it will blow over’. Common sense could tell you we’re not going there again. This was a failure, people didn’t get it, let’s go back to status quo.

But I knew that I could not afford to be misunderstood in this case. This is a community that I come from, this is a community that I represent every time I walk into a board room; every time I walk into any room; as a storyteller. I am here to represent this audience, and I have to explain what my intention was here, and I have to get more people to read this story. So I wrote a letter, which was really risky, and I was very nervous about it because get it wrong twice and just forget about it. So I wrote an open letter in response to all the negative press around it, and it was so fascinating because on my Instagram in the captions people were just coming for me. The model finally chimed in and said “For anyone that cares to know, I’m Black and French. Am I not Black enough to wear braids?” [pause] and I just wanted to say thank you. So as soon as she said that, I jumped in and said this is a larger conversation about colorism, because a lot of the people that came forward to drag Teen Vogue and me came from Black Twitter, and it’s like hold on—am I black enough to wear braids? But she’s not black enough to wear braids? Did you read the story? Because its not actually trivializing braids, its not actually saying that braids are just a fun summer trend, its so much deeper than that, and so I was really grateful to have the opportunity to change the narrative around that particular piece and hopefully to remind folks that

"before you retweet, before you drag, make sure you do your research, make sure you actually read the story, you’ve taken the time to actually form your opinion about the work."

-Elaine Welteroth

Because then the dialogue is so much more constructive. I’m all for being called out to have a conversation if we’ve missed something, but make sure your doing your part is all I’ll say.

[Amy] And I did my research and I was so happy, and I feel like people if they would have done the research and read your beautiful, personal, emotional story about going back to the motherland, and getting all that, they would have felt empowered.

[Elaine] And eventually they did, and that’s what felt so good about it, eventually they did, and as you see it take baby steps. I also don’t want to dismiss the fact that Teen Vogue had a lot of work to do, and yes I was a part of that, so yes I had some bruises and nicks along the way, but that’s part of progress, you know? And you can’t give up just because somebody doesn’t get it, or you get some backlash. It doesn’t mean you should stop. You have to keep pressing forward, so that’s what we’ve done, and eventually now people get it, and they’re like “Teen Vogue is leading the resistance”.

[Amy] They are!

[Elaine] No it not, its because I have an amazing team.

[Amy] It because of you the leader.

[Elaine] Its because of woke—insert another word for woke-- people that work on our team. Seriously we have the best, best, best young people that work on our team.

[Kim] That was a really great answer. Now that we’ve kind of set it up for cultural appropriation, I don’t think we’ll be able to get through all the images. We can come back to it. Just speaking about cultural attitudes in our fashion industry family, I know my partner in this event, Becca, was particularly moved by this quote, and brought it over to me, and we just thought this is a great space to address this quote because its not just Marc Jacobs that feels this way, this is sort of dismissive or maybe just not understanding what’s at stake when it comes to cultural appropriation. He just doesn’t think its that big of a deal, and he’s certainly not the only one. So the quote that he had was:

“There seems to be this strange feeling that your can be whoever you want as long as it’s ‘yours,’ which seems very counter to the idea of cross pollination, acceptance, and equality. Now you can’t go to a music festival with feathers in your hair because it’s cultural appropriation.”

So this sort of aggravation or exasperation with the fact that things are becoming sort of “overly politicized” nowadays. That everything is off the table when it comes to cultural inspiration, or design inspiration rather. You have creatives like Marc Jacobs who feel that the intent isn’t to be racist, or to exploit anyone, they’re just inspired by a look, or a culture, and it flows into their work, but something gets lost in translation along the way. I want to talk about it and work through this quote. I want to emphasize its not to drag Marc Jacobs, it’s just a good example of many of the general attitudes going on in our fashion industry when it comes to inspiration for ideas and aesthetics, a look, and why this can veer into cultural appropriation territory and be damaging.

[Amy] I’m just going go ahead and jump in here. I think you have some great things too—so I love this idea of cross pollination. Marc is like “yeah cross pollination,” if you really honestly want to cross pollinate, you’re going to look into a culture that you’re trying to get inspired from, and if you did that, if you honestly, really cared enough to look into “Does that mean anything? Does a war bonnet mean anything? Is it okay if a semi-naked model wears that? Or a man wear that, or whoever.” Researching that is very easy. We have google, you can see that it is inappropriate, and to wear a war bonnet is an honor and you’ve earned those feathers, and they’re sacred. The eagle is very sacred to us, so yeah you know its kind of this whiny comment of “we can’t wear feather because we’re going to offend someone. We’re going to offend a marginalized group of people.”

"This is our culture. If you really wanted to cross pollinate, you wouldn’t wear war bonnets, and feathers, and stuff like that. You don’t want to really live our lives, and see what we go through as a marginalized person."

-Amy Farid

And I feel that’s with everything, when people want to wear certain clothes that look hip hop, and they want to wear braids, and its like “yeah I want to do that, but I don’t want to deal in those real spaces that those people have to really endure growing up,” and walk in those shoes.

That’s why I love Hood by Air- that whole street wear thing that happened. You know people really bought into wearing these clothes that you know are made popular by these young kids in the streets who don’t have the money to buy the things that they see, that they want, so that juxtaposition is such a trip to me to see that. You know, do your research. Don’t wear feathers—wear flowers. Flowers are cool, bees can pollinate. That’s my whole thing, festival season comes around and I’m like wear flowers, not feathers. You can do that.

I’ve been in situations on set, like you do festival lookbooks now, you know for fashion stuff. It’s a whole machine now, you make money from that, all you designers know that. There have been moments where they’ll be like “we have these headpieces, these headdresses,” and I’m like “girl, no,” and they’re like “oh yeah girl, whatever you don’t want to do,” and I’m like “this should not be happening at all like take it off the site.” I’m lucky there are certain fashion brands that listen to me, and that care about that, so me being in these spaces, and having people talk to me is awesome, and just comes back to ignorance. People are just ignorant, and I’m ignorant too.

[Kim] Or laziness.

[Amy] Or laziness yeah, its like come on.

[Kim] Not wanting to do the work,

[Amy] Yeah not wanting to do the work, and just wanting this aesthetic because its shallow, like its just feather, it doesn’t get any deeper. I was once on a plane going to a very amazing photo shoot, on a very amazing island, and I was sitting next to this stylist. I was working for a very large lingerie company, and the stylist was telling me—very large not like plus sized you know, just a big lingerie company.

[Anastasia] I wish it was plus sized.

[Amy] I now right, like they’re cute bras. So the stylist was telling me about this model who has her own line, and she was doing a photo shoot in Italy, and she was like “Oh my god, she has this beautiful war bonnet that she bought.” She didn’t say war bonnet, she said “Indian headdress that she bought in Italy. Its like floor length the whole thing.” This was my first time travelling with this client, and it was like one of my first times flying business class, and I’m very bougie. So there are two roads that you walk in this life, right? You’re like “down, Native, brown pride,” and then you’re like, “Cool I’m in this space, and I want this job, and I need this money. Mamma needs to pay bills,” but I have this time, I can talk to this woman about this. We met 20 minutes ago, and now we’re on a flight to LA, right? And then a whole other flight, and a whole other voyage together, and I’m like I have to say something. I had knots in my stomach. She told me “yeah we did this photoshoot,” and it was bikinis of course “and we shot in Ibiza and she has this big war bonnet,” and I was like “You know that’s not cool right?” I said it, and she was like “really?” and I was like “yeah, that’s really not cool. Like if she wants press, and she wants to keep that, then she’ll get it, if she wants that. If she wants that negative press believe you me she will get it, so if that’s what you want to do you’ll get that.” “But just letting you know” so I told her, “those things are earned, feathers are sacred, feathers are earned. Eagle feathers, how did you get that?” I didn’t even go into who stole this regalia, whatever. I just told her you can’t, and I never saw it. I saw her publish this look book of this model’s bathing suit stuff, and they never printed those pictures from what I researched. I never saw them, and I was like ‘did I make a difference?’ She listened to me, and she went back and told this model, and that was her favorite thing. That was her piece that she bought for the shoot, this was the major thing and it didn’t happen. I kept looking, I still do now and then before I drag—and I’m not going to, but yeah it never came out, and I saw her bikinis, and I never saw those images. And that for me was one thing, like I’m in this space. I did it. I got to make a little bit of a mark, you know, so do it.

[Aurora] That’s a big mark.

[Amy] That’s what it is, these people don’t mean to be […] it’s the ignorance you know. Instead of doing your research, you want to be lazy about it and be ignorant and unwoke. Sorry that was so bad, anyway so yeah.

[Aurora] I mean that’s a really intense quote. He’s someone who’s been involved in these conversations. He’s not stumbling around being like “really, what?” and some people can have this conversation, and listen to what we’re saying, and disagree. And when I look at his words—I’m a pretty literal person, cross pollination, that’s a tangible exchange, but when I see these pictures like the ones that were on the slide before this, that we saw for a couple seconds, there was no exchange there, that was stealing. I think he really needs to really think about what he’s saying, and the other word was equality, and

"when we take ideas from people who don’t have the means to promote their own ideas themselves, we’re not displaying equality."

-Aurora James

If any of these designers are inspired by a different group of people, they should go out and cross pollinate with those people. You know involve those people. I can promise you the embroidery by the people that you are inspired by is going to be way better than the people you’re getting to do it in China or wherever else, and actually help and support a community, so I mean I don’t know. I think what’s so important is actually sitting at a table with people you disagree with as well, and not just always having conversations with people you’re on the same page with, because its going to take an actual, real conversation with someone like Marc Jacobs, who has that opinion, to say “this is why we’re hurting, and this is why this maybe isn’t okay, and you turning my culture into costume doesn’t feel good.” But

"some people have never had that experience themselves because they haven’t been marginalized in certain ways, so they can’t relate to why it would be a big deal."

-Aurora James

[Amy] Or around humans that are from that culture that are like “no that hurts, we’re real people that exist, we’re not mascots,” it’s being so divided from people. And that’s why diversity in fashion is so important, so you have that voice like me on the plane telling you “girl don’t do that”.

[Aurora] And I think you were talking about your voice, and it’s really just about people speaking up, and earlier in the green room I think I wanted to know, and I think everyone wants to know, how these bizarre photo shoots happen like with blackface, was there no one on set that was like, ‘hey um, can we just talk about this for a second?” You know its like at American Idol auditions when that’s person’s signing, and it’s horrible, and its like somebody say something, and nobody is saying something, so I think it really takes all of us to be that 22 year old in the board room that blurts it out, and I know in my own life I’m definitely that person, sometimes its annoying, but the way that it impacts, not saying something, as hard as it is for you to say something, not saying something is going to feel a lot harder for a lot of other people.

[Amy] And to yourself, if I wouldn’t have said that I would have still held that

[Aurora] You would have held it, and then it would have been on Instagram, and all of these young girls would have seen it and been like, “why do I feel this way? Why is my culture being hyper-sexualized, and why are we not included in this narrative unless it’s with boobs or at a music festival?”

[Anastasia] It brings up an interesting question though because there has to be people with that point of view at the table to question it, and there isn’t. It’s very rare that you see a lot of diversity seated at the table, its very one sided.

"You can’t have people telling your story when there’s no one who’s had your experience seated at the table to tell it."

-Anastasia Garcia

[Aurora] Because also like you know, as a black woman I know with that hot mess story, which was kind of a difficult one, but like if that’s how you’re presenting yourself, and you’re a black woman, and you have a wig like that, and you have nails like that, you’re not even going to get into the building because it’s not accepted. So when people put those images out, and are like oh check it, it’s a slap in the face because you’ve been changing yourself your whole life to fit in, and you’ve been buying all the products they’ve told you to buy, so you look like more the girl they’re usually portraying.

[Elaine] Very quickly, when I read that Marc Jacobs quote the glaring thing that stuck out to me was the white privilege. Privilege is not having to see what doesn’t directly affect you. And we live in the world of google. You can easily educate yourself if you don’t understand it because the world has not made you face it, this type of discrimination, then there’s so much research you can do, you can talk to people that better understand before you then speak out again on how you don’t understand it.

[Amy] You’re crying for attention. I mean its such a whiney little quote, like “girl, really?”

[Elaine] There’s a lot of things you can wear. There’s a lot more you can get away with than I can. There’s a lot more opportunity for you than there is for other people that come from these marginalized communities.

"It’s important that whether you’re white or a person of color, to own your role as an ally, to take your time to understand someone else’s plight, especially when it doesn’t affect you directly. Otherwise its just an egregious display of privilege."

-Elaine Welteroth

[Aurora] I mean he’s also in such a power position too. If he was like, “you know, I’m going to make these jackets like actually in this place, with this embroidery with these people,” I mean talk about job creation, right?

[Amy] How amazing would it be if he did that? Come on Marc we got you boo, we’ll google it for you. We’ll ask Alexa and Alexis we’ll sort it out for you.

[Kim] You can join the fashion and justice workshop.

[Amy] Yeah perfect Marc if you’re watching [points to camera]

[Elaine] Invite him to the next one, to Aurora’s point we’re in an echo chamber. We’re talking to ourselves about stuff we already understand. Its important to invite those people to the table, for us give them a moment to hear them out, and then also to create a safe space to actually help create progress. He has the power. We should be incentivized to actually want to reach him with this message behind closed doors maybe or in a safe space, so he can reach the masses with a more conscious message.

[Kim] So as we wind down our conversation before we go into q&a, and we’ve already moved towards solutions, but I just want to with each of you to speak once again in closing with some of the highlight work that I’d like you to share that is proposing solutions for those of us outside the echo chamber, who want to know how can I just do better. So you spoke about this earlier, but these are some images form the ‘Cultural Appreciation” spread that you did, so if you could just summarize this once more now that everyone has an image to what you were creating this beautiful, pivotal piece in response to cultural appropriation.

[Elaine] Beyond this amazing story that we’re really proud of, in order to do more of those, it required changing the makeup of the team behind the scenes. Changing the demographic of the table that was having conversations to land here. I think we’ve all kind of touched on this, but it all comes down to who’s at the table to speak up for who, and for me

"its very important when I look at my masthead I want young people to open the masthead and know that there’s someone on that team that can speak for me."

-Elaine Welteroth

Being in a position now, an empowered position now, and being able to create opportunities for other young people of color, or of diverse backgrounds, has been a key focus for me, and other managers on the team, and its all a collective team effort. We had to change the zeitgeist culturally at Teen Vogue in order to change the storytelling that you’re seeing. So it really started with changing the makeup of the team, and I’m so, so proud that we have an extremely diverse team, and we learned from each other, and that’s how were able to continue doing the incredible work that Teen Vogue is doing these days.

[applause]

[Amy] Thank you, thank you, thank you, I love you. So yeah this is the picture, the one from behind with the eagle feather, that I was going to come for Teen Vogue, but it was even tighter so I didn’t get to see any of her regalia. Also I wanted to also mention when Native peoples, American Indian people, dance, those are not costumes, and I’ve heard them called costumes before, its called regalia, and we’re not dressing up as something so I just wanted to say that. It’s really important, I’ve heard it being called costumes before, and that’s not right, its regalia. But I feel like having allies, and Elaine is in an amazing position to create an amazing magazine to showcase all these brown beautiful people, and I feel like that is what we can all hope for, whoever you are, whatever space that you are in, you can be an ally, you can educate yourself.

Don’t be ignorant. Find out about other cultures that you don’t know—if you feel that, that’s your intuition. Listen to that, that’s your gut. Take that in, and really research that before you think. If you are designers out there, if you’re young, if you’re at the Parsons, the future is yours and you have the power to change that. You guys can do this, we can all do this, everybody here, and that’s why I’m so excited we have this here during fashion week. You guys are the new change makers in this industry, and it starts young. It starts with my daughter, with your daughters, your sons, your grandma, whoever. It just starts with education and when we start them young, and you guys are young, and you’re at this school, you can do this. You don’t have to fall back into these old stereotypes of fashion, and you know you can do this, the world is ours and it’s becoming more inclusive, and its up to you, to everyone. People of color, women of color, Caucasian people, like we love the Caucasian people, we need those Marc Jacobs, you need a good white friend, you know? Cause that helps you, that’s what we need, right? Because we might not have that voice, but you all do, and you can help us get to this spot. Becca’s why we’re here tonight, good white friend, that’s my friend that’s my girl, props to the good white girls and my Lena that’s my friend that’s my good white girl.

[Kim] You know what just to Becca’s credit. When we were first organizing this I was like “you’re gonna be on stage with us right?’ And she was like “no this isn’t a space for me, this is for you all to have this conversation, I want to give you all the space.”

[Amy] Becca McCharen-Tran, who by the way, if you have not seen her show, was the most diverse beautiful show that I’ve seen yet during this fashion week. Body diversity, everything, like hands down, and you’ve been doing that for years girl, you’re like whatever, but seriously that is the future. You make clothes for everyone, doesn’t matter. If you are young designers, make clothes for fat people, like you’re just going to make more money. Learn how to shape around a big body, do it, you’re just going to make money. It’s just good, we like to wear cute clothes.

[Anastasia] It’s a 20 billion dollar industry, just letting you know.

[Amy] Like come on, just do it. Thank you.

[Kim] Aurora, well we have a visual when it comes to your design ethos. How does this all matter for you, what does this all mean for you.

[Aurora] The knockoffs? [audience noise]

[Kim] How does this impact your design ethos, what you’ve worked so hard to do and build, the change that you’re making?

[Aurora] Well the Zara one was the first one that really happened to us, and when I saw it one of my old interns sent it to me, and she was like “oh man what is this, so brutal,” and my heart stopped, and I was like ‘oh no.’ I just thought of like how big Zara was, and I was like ‘there’s so many of those that must be on the shelf right now,’ and ours had sold out, and we were working really hard in Ethiopia, which had just declared a state of emergency, to get more here. People were showing up at work despite there being a state of emergency to try and push through and get shoes to the customers, and maintain their job, and maintain their income. So I posted it with the caption ‘stolen from Africa’ because I felt like--

[Amy] Drag them. That’s what they did.

[Aurora] It was our design, and we were making it in Ethiopia, and we were working really, really hard at it, and they were just like *boop* and suddenly they were all over the world, and we’re talking like a million of these, and that sucked, it really did. There was a lot of press around it and it started a bit of a larger conversation: What does it mean when you knockoff something, what does it mean when you buy a knockoff, and is imitation actually the highest form of flattery? Because a lot of people were like ‘you should be flattered.’ But it doesn’t feel like that. Flattered because Zara liked it? Zara likes everything, they have to. They have like a million things in there all the time, they’re carnivores, so no, that’s not flattering.

And then when the Steve Madden one happened, it was the same situation, the shoes were sold out. We had hundreds of customers that had pre-ordered that pink shoe and Steve Madden was like *boop* and sold it to Nordstrom which was the same retailer that I had. Ours were 265, and theirs were like 65 dollars and made in China, and I was like ‘how am I supposed to compete with this?’ This crazy dialogue started happening on my Instagram where some people were like ‘listen, I love fashion I want participate in fashion, but I can’t afford to spend 300 dollars on your shoes, so I have to get the 65 dollar Steve Madden shoes.’ and I had to take a step back and think about that because the price point of a lot of fashion is in and of itself exclusionary, but just because you like something I designed, doesn’t give you the right to steal it from me, and you can’t empower another person to steal it from us just because you want it to be cheaper. I priced it that way because that’s how much it costs. These aren’t arbitrary prices, we pay people a living wage. Everyone that makes our shoes has things, and you can pay someone 85 cents and make it in a sweatshop, and end up with 65 dollar shoes, but that’s not the business that I wanted to have.

[Amy] Which is amazing.

[Aurora] Amazing yeah, but what do you do in that situation? We were incredibly lucky because we have a very active social media following that’s very engaged, that’s not down, so they started, as soon as I posted my Instagram story about it, writing to Steve Madden. Their whole Instagram totally blew up. People were like “how could you, this is insane,” people were calling the stores, we had really great press around it, and I actually found out that one of the publications that covered Steve Madden knocking us off, the same day got a phone call from Steve Madden saying that if they didn’t take the story down, they were going to pull all of their advertising.

That’s when I realized this is no joke, and I also realized how much courage it takes all of us, and how much courage it takes the media to stand up against these things, and it’s way more layered than a lot of us know or understand. Steve Madden was a huge advertiser for these people, and I fully expected them to take it down, and they didn’t. That was a Friday, the Women’s March on Washington was a Saturday, and that’s when they told me they were leaving the story up, and by Monday the shoes were pulled from Steve Madden’s website, and that was just from you guys. There was no lawyer involved, it was just from individual people calling Steve Madden, writing on their Instagram, our voices have power, and that’s what we need to realize.

Because of these people writing and calling, people in my workshop were going to be able to continue to work, and make these shoes because the knockoffs were getting pulled, and it does have an impact. Those knockoffs do have an actual impact on your business. I know that its easy to go into these stores and buy stuff, but just think about what you want to support, and

"know that every time you spend your money, you’re voting with that money, and that exchange is a form of empowerment."

-Aurora James

When you go to Zara, or Forever 21, or any other company, you’re choosing to spend your money there, you are exchanging power with that business, and in 2017 we need to make sure who we’re giving power to.

[Kim] Anastasia?

[Anastasia] The brain processes an image 60,000 times faster than a word

[Amy] Wait repeat that, what’d you say?

[Anastasia] The brain processes an image 60,000 times faster than it does words. So for me, which is all I can speak from, it’s about understanding that we are inundated with imagery, and making that imagery something that will empower people, and that will support communities that need to be supported and empowered.

I try to think of three things whenever I’m working, and the first one is to realize my own biases, which isn’t always easy to do, but we all have social programming, and it doesn’t just go away unless you deconstruct it. Sometimes facing it is not easy, and sometimes people around you will call you out, and it will be uncomfortable, but it’s important before you address anything to do the work within yourself.

Number 2. As we’ve all kind of talked about—speak up. Again, I promise you there will be times where it will be uncomfortable. Most of the time it will be uncomfortable, but you have to keep doing it because

"we need to hold each other accountable"

-Anastasia Garcia

we need to share our experiences with people that don’t have them because it’s the only way we’re going to create any kind of change.

The third one is to be the change. If you’re designing clothes that you can’t wear, you need to change how you’re designing. If you want to support marginalized communities, you need to be working with marginalized communities. You can’t look around and wait for things around you to change, you have to change them and its not always going to be easy, but it’s the only way things are going to happen.

[Kim] So how much time do we have for q& a? I know we’ve run over this—zero?

Just a few questions, if people can come line up. We’ve set up two microphones here so if we only have a few, we’ve gotta make them good. This is a lot to work through. We’ll do the best we can since we’re cutting off time, so just a few questions.

[Question 1] Hi, so at least it seems like you guys are very like supportive, and lift women up really well so I was wondering, how you suppress the ingrained idea that women have to be in competition with each other, and how you’ve done that with your work.

[Amy] Is this a question for all of us?

[Question 1] Yes.

[Aurora] I’ve never felt that. Becca and I did the CFDA Vogue Fashion Fund together, and I was just thankful there was one other woman, we were the only two women, so I was like “we have to do this.” It’s like, all ships rise with the tide, you know, so I’ve never felt that competitive thing, like what are we competing for? There’s enough pie for all of us—or cake. What did Courtney Love say? She was like, “I want to be the girl with the most cake,” I don’t feel that, I’m cool to share.

[Amy] Me too. I’m all about women empowerment, and my mom was really into “be independent, do what you have to do,” there was never any weird shade towards other women so I love empowering other women.

There was a beautiful woman walking down the street last week in Soho and she had this beautiful flowy yellow dress on she was walking, and I was walking behind her, and I had my kit, when you do hair you have this kit all this shit, and you’re struggling and I look like a mess, and I was following this woman, it was just such a beautiful dress on these filthy streets the bottom of her dress was getting dirty, and we were at a crosswalk, and I stopped and said “you look so beautiful, I just have to tell you that,” and she was so taken aback, and I was like maybe no one else would tell her that, or maybe her good girlfriend wouldn’t, maybe she doesn’t have any good girlfriends. She was like, “oh my god thank you” and I was like, “you look gorgeous,” she looked beautiful, it was just a magical moment, so yeah, I’ve never really had that.

[Kim] We have time for one more and then—okay we can do a couple more because I know we have a time crunch for one of our guests so we can just sort of speak privately afterword.

[Question 2] Hi, my name is Lai and I thank you all for sharing all your experiences and everything. I’m from China, and I know when I heard your comment that embroidery made in China is of less quality I just to give more information, because I felt kind of hurt because China was actually the earliest country who discovered silk, and we used that for embroidery first, we have really famous embroideries, actually one of our most famous crafts, there are four different types Su Xiu, Xiang Xiu, Shu Xiu and then the last one is – I forgot [Yue Xiu/Guang Xiu], but sorry they’re called Su Xiu in general so they’re really like the real authentic Chinese embroidery so they’re really high quality, so

"I just wanted inform everyone that so that China is not always associated with bad."

-Lai

[Aurora] I think it would be so amazing to like see traditional Chinese embroidery done that way, you know? Make that, have someone do that, showcase that. Let’s see that amazing skill from those people that have been doing that multi-generationally.

[Lai] Exactly, so think that it’s our responsibility to really speak up for ourselves and embrace that into our work until the world knows this is what authentic Chinese craft looks like.

[Amy] Thank you for that, I agree.

[Lai] And then about social media, it does have a really powerful impact, and as you mentioned the nuances are not always reflected. It is definitely our responsibility to do our research, we cannot expect everyone to educate us all the time, although you take patience to educate other colleagues who don’t understand your culture, but I think that its also important to realize there’s a difference, intention matters a lot. We have an assumed intention but our action might have a consequence that’s a different way. So I think its really important to recognize that. For example, I have a friend that posts on social media “queen of Chinatown,” and its this blonde girl singing the entire time, her intention is definitely not to oppress Chinese people, or say “this is the queen of Chinatown,” but the impact in brings is definitely not preferable, so I think it’s important to like recognize that. That’s just my interaction with you guys, not really a question, and I do appreciate lots of things you’ve shared, so thank you.

[Amy] Thank you.

[Kim] We have time for one more and then we can talk afterword.

[Question 3] Hi, am I loud enough? So you guys were so inspiring that I kind of wanted to add my own part of the conversation as well. Growing up with a disability, one of you guys were talking about how you saw the black dolls and the white dolls, where were the dolls in the wheelchairs? Where are the magazine covers of people with disabilities on it? Growing up with a disability that was so visual, I got a lot of attention that I didn’t want. So how do we spread the message for people with disabilities in the way that we want to be addressed. In the same way as with cultural appropriation, how do we want to be addressed? Because I feel like with a lot of us, we either are too embarrassed to talk about that, this is something that’s very important, but its also something that affects everyone. Whites, blacks, females, males, but no one is really talking about it. So I was wondering how you guys would address this situation?

[Elaine] We should talk about doing a story.

[Question 3] Please, please.

[Amy] This is the one, I mean I’m telling you, I have a daughter that’s seven and she will see people that look unlike we look, and she’ll ask me because she doesn’t see people that don’t look like her on magazine covers, and its again the imagery.

[Question 3] I work with kids every day, and they will always ask “what’s on the side of your head?” and I have to explain in the most basic sense for them to get it. I’ll tell them “you know how when someone wears glasses, they can’t really see? Well people who wear hearing aids can’t really hear.” That’s the end of the conversation, they’re satisfied with my answer.

[Amy] Totally okay with it.

[Question 3] Exactly.

[Amy] Because they want to know, “its different to me, what is that?” and when you have that conversation you also have to be right with yourself, to have that, and not get into your emotions about it, to be like, “this is great, I need to speak to these children so they realize this is what it is. its not a big deal, I look like this, I have that, whatever.” Once you have the communication and the knowledge. Thank you for working with children.

[Question 3] And something else that while growing up my mom always told me was since I always got so much unwanted attention for how I looked, my mom always told me never judge someone for how they look, it’s so stupid. It’s like that tells you no information about them, so me from the year of six, learning not to stare or not to ask rude questions, its like my fundamental. And this idea that nobody else has been brought up to think like that is shocking to me. So Elaine, if you ever want to do a cover shoot— [laughs] thank you guys so much.

[Elaine] Let’s exchange emails right after this okay

[Amy] She walks the walks and she talks the talk. It’s not just like fake. That’s why Elaine is dope, I love you.

[Elaine] You’re trying to make me cry, all of you are trying to make me cry.

[Kim] Well let’s keep going afterword but we’re out of time.

I want to thank all of you for being here, this is such a nourishing discussion, such an important discussion, and it would be nothing without you all and it certainly wouldn’t be anything without our panelists. If you could just help me in just thanking them. So, thank you, the conversation continues.

[END]

Keep the #FashionJustice conversation going!

Follow our speakers:

And us :) @chromat

Thank you to #TheNthDegree!